Resource

Infusing well-being in the flow of work POV

This research point of view was written by The Limeade Institute — a team of researchers and advisors with deep expertise and advanced degrees in the areas of organizational psychology, psychometrics, data science and other related fields.

Introduction

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed the landscape of work when many in-person workers switched to remote work arrangements and frontline workers began working under more difficult conditions. According to researchers, the pandemic exacerbated existing stressors and inequalities for workers (Nieuwenhuis & Yerkes, 2021). On top of the increase in stressors, people had less time for personal well-being care and a greater need for it than ever. To counter the increase in stress and limited time for well-being activities, we propose that individuals and organizations will be successful in addressing employees’ well-being needs by infusing well-being directly in the flow of work.

The “flow of work” refers to all the interactions and behaviors that employees engage in throughout their workday.

The flow of work includes each interaction employees have with their company, leaders, managers, the people they work with, policies and tools they use. Infusing well-being in the flow of work involves designing the flow of work around employee experience to improve employee well-being, work performance and employee productivity. Well-being, which Limeade defines as a combination of feeling good and living with purpose (Hamill, et al., 2020), occurs when people experience positive feelings and life conditions that enable them to thrive and reach their potential (Charie et al., 2018). Investing in well-being at work can help employees gain and maintain their energy while enhancing positive impacts of work on life outside of work. According to Limeade research, increased organizational care positively impacts employee well-being as well as business results (Limeade Institute, 2019).

In practice, well-being in the flow of work enables employees to find moments throughout their workday to engage in activities that support their well-being. The path to well-being in the flow of work can look different depending on the organization and team; however, the goal of supporting well-being remains the same. In the flow of work, well-being can be supported through personal connections, organizational resources, seamless technology and a culture of care. Infusing well-being in the flow of work also means removing barriers that impede well-being in the flow of work. Removing barriers can involve integrating technology into the flow of work so that employees do not have to sign into multiple tools to easily access well-being support during work.

Well-being is often conceptualized as an outcome; however, we suggest well-being should also be something that people do. To bring a well-being focus, organizations, managers, leaders and employees must prioritize well-being in their behaviors and throughout work processes; i.e., make it a part of their everyday work. This means always considering the impact of organizational decisions such as roadmaps, product and service offerings, and human resources policies, on employee well-being. In addition to considering well-being through policies and processes, leaders and, in fact, all employees have a role in creating a well-being culture that supports healthy behaviors. This culture specifically should support workplace routines and habits that include integrated well-being moments.

In this paper, we discuss the utility of including well-being in the flow of work and describe what needs to be in place for well-being initiatives to be helpful and not disruptive in the flow of work. We also suggest a shift from individual-focused well-being approaches to more integrated, accessible well-being approaches that ultimately benefit people and business outcomes.

The case for well-being in the flow of work

First, it’s important to demonstrate the power of infusing well-being in the flow of work. Research from the Limeade Institute and within the field of organizational psychology demonstrates the benefits of whole-person well-being on the employee experience (Limeade, 2021). Providing well-being support in the flow of work can have positive results:

- Increased employee focus during subsequent job duties (Zito, Cortese, and Colombo, 2019)

- Employees are 69% less likely to search for a job when they feel their organization cares about their well-being (Harter, 2022)

- Increased productivity (Well-Being Limeade, POV; Shi et al., 2013)

- Successful business outcomes (Well-Being Limeade POV; Shi et al., 2013)

- Improved resilience when faced with adversity (Huang et al., 2019)

- Support for diverse employees (Fletcher, 2020)

- Job satisfaction (Maggiori et al., 2013)

- Higher affective commitment (Meyer & Maltin, 2010)

- More socially responsible and sustainable behavior (Conti, Arcuri, & Simone, 2018)

Neglecting to support employee well-being can have profound consequences for employees and organizations. In fact, negative experiences at work can have a spill-over effect to an employee’s home life and vice versa (Sirgy, 2020). The following negative outcomes can occur when employees are not receiving adequate well-being support:

- Employee burnout (Harter, 2022)

- Health complaints (Zwetsloot, Leka, & Kines, 2017)

- Absenteeism (Berry, Mirabito, & Baun, 2010)

- Workplace accidents (Zwetsloot, Leka, & Kines, 2017)

- Higher insurance premiums (Berry, Mirabito, & Baun, 2010)

- Employee turnover (Harter, 2022)

There are two major barriers to infusing well-being in the flow of work. The first barrier is a lack of time in the typical work schedule. The second barrier is a lack of easily accessible well-being tools. Addressing the first barrier, employees often report not having enough time to fully take advantage of existing well-being resources, despite 68% of employees preferring to engage in well-being-related activities at work (LinkedIn Learning, 2018). Similarly, another survey found that the average employee only has 24 minutes a week to engage in learning activities to increase work well-being (Josh Bersin, 2015).

Furthermore, many well-being applications include accessibility barriers such as separate login screens that are not integrated with the employee’s work technology. Even if employees want to utilize well-being resources at work, they may not have the time or support to incorporate well-being into their workday. The integration of well-being in the flow of work would remove these barriers, enabling employees to achieve the positive benefits of work well-being, which would then contribute to overall life well-being.

A view into the future of well-being in the flow of work

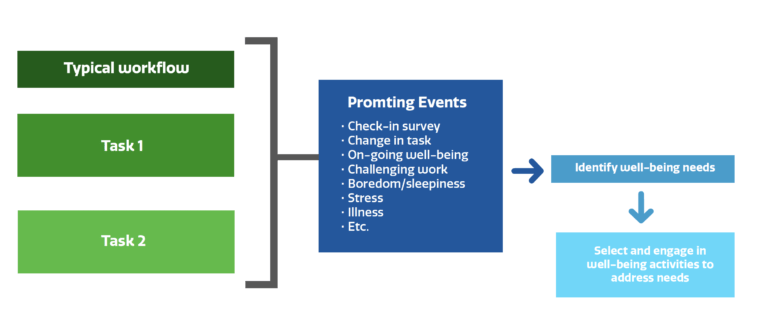

Every job has a typical workflow comprised of tasks that must be completed to successfully meet the requirements of the job. However, traditional workflows allow for few breaks. To counteract the demands of the typical workflow, organizations should infuse well-being in the flow of work and find ways to prompt employees to do so. Prompting events can either be planned or based on a need or event. Planned prompts include check-in surveys, changes in task and ongoing well-being goals. Need-based prompts include challenging work, stress, boredom or sleepiness, and illness. Many different prompts can nudge the employee so they can focus on their well-being. With well-timed nudges, employees will have reminders and additional support while establishing habits that support well-being. Organizational care and technology can help employees become aware of well-being needs employees may be unable to identify on their own. During feedback sessions, managers may identify areas for an employee to improve such as work-life balance or stress management. Employees can also explore and identify their well-being needs by taking a survey to assess their current well-being. After identifying their well-being needs, employees can select and engage in well-being activities that address their needs on the job.

Here is an example of well-being in the flow of work. Devon H. is a sales manager for a software company. During the typical workday, Devon has 2-3 meetings with customers, plus ticketing and documentation, and communications with direct reports in both email and messaging tools. In line with the company well-being culture, meetings begin 5 minutes after the hour to include built-in time for breaks. As a manager, Devon always begins 1-on-1 meetings by checking in on how his direct reports are doing. Based on how Devon’s direct reports are feeling, plus their work needs, Devon finds flexible ways to support employees and adjust their workload.

Each workday, Devon responds to a quick one-question survey to check in and assess his well-being. Based on Devon’s response, a break to address his well-being needs is suggested through a well-being application. For example, if Devon’s response indicates high stress, then a push notification suggests he take a meditation break or reach out to his manager to gain support. Through machine learning, the application recognizes that Wednesdays are the busiest and most stressful for Devon, so the application sends a note to Devon asking permission to book an extra break from work on Wednesdays. Alternatively, the application could ask permission to shift meetings to another day of the week to relieve Devon’s Wednesday stress.

Over time, Devon can see how his well-being fluctuates over the course of weeks and months. This information can inform Devon of changes to his well-being and offer suggestions for infusing well-being in his work. As a manager, Devon also receives well-being check-in survey results about his direct reports. For instance, if one of Devon’s direct reports responded with substantially lower well-being compared to usual, Devon will get a nudge to schedule a quick check-in with the employee. Devon also begins all meetings with direct reports with informal conversation and asking about how the direct report is doing. According to research by Harvard Business Review, employees who report a lack of informal conversations were 19% more likely to report a decline in their mental well-being.

Well-being in the flow of work can also be applied to all employees regardless of organization, position or work arrangement. Tara W. works on the floor of a manufacturing plant. Her company supports well-being in the flow of work through policy, technology and culture. Policies such as ensuring consistent shift schedules so that employees can have certainty when planning their personal life and family activities (McHugh, Farley, & Rivera, 2020). Technology supports Tara’s well-being by providing nudges for well-being activities that support recovery during breaks. For example, healthy snacks and short walks or stretching could be suggested through technology and then supported through the organizational environment. Employee well-being is also supported through culture at the manufacturing plant. Teammates are encouraged to check in with each other, and opportunities for additional breaks are available when needed. Employees are also trained and encouraged to provide job support and mentoring. Further supporting well-being culture, managers and team leads work with employees to provide flexibility and any needed personal support or remind them of company resources such as counseling or employee resource groups. These improvements can enhance employee well-being, which in turn can reduce absenteeism, workplace accidents and operational issues.

Measuring well-being in the flow of work

Like any strategic organizational outcome or key driver of results, it is important to measure well-being in the flow of work to ensure consistent awareness of utilization and impact, as well as business outcome benefits. Employee well-being initiative outcomes can be measured through varied resources — reporting that tracks awareness, utilization, as well as effectiveness measures. Examples include participation, behaviors, biometrics, and health benefits utilization and costs, as well as employee (health/well-being assessment) survey responses and/or employee sick days. Aligning with valid measurement approaches, these resources should all be measured across multiple dimensions, such as organizational function, geographic location, and workforce demographics, while protecting employee privacy.

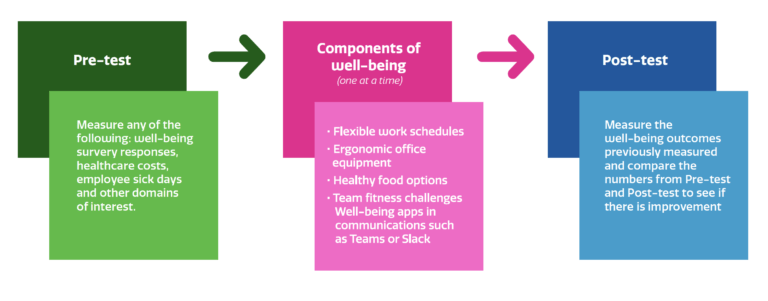

HR managers and organizational leaders want to ensure their well-being initiatives are effective and adding value. Measuring the effectiveness of a well-being initiative can take many forms; we recommend a pre-test/post-test design as it is both simple and rigorous in measuring change. 1) Identify and then measure the outcomes; 2) implement a component of well-being into the flow of work; 3) measure the outcome(s) of interest using the same or similar methods as those used in the pre-test. Consider changing only one component at a time for measurement accuracy. If more than one component were implemented between pre-test and post-test, it would be difficult to separate out the effects of the individual components.

Recommendations:

Encourage employee goal setting to improve health and well-being at work

One of the most consistent findings across decades of research is a simple principle: if employees are given the freedom to set clear and specific goals for themselves, they are more likely to achieve those goals (Basadur et al., 2012). Although frequently discussed in the context of boosting productivity, goal setting has enormous implications on well-being. Regardless of their objectives, goals are inherently motivating; they focus attention on specific tasks and set people in motion to accomplish them (Kanfer et al., 2017; Locke & Latham, 1990). Employees can better pursue their well-being goals by creating smaller steps and habits along the way (Putnam, 2015). Organizational culture and technology can serve as supporting factors for employee well-being, especially by making goal-setting simple, repeatable and habitual.

Organizations can gain the most value from goal setting when it becomes a habit, rather than a one-time behavior. A 2019 study of software engineers demonstrates the value of continuously setting and checking in on goals (Meyer et al., 2019). Each morning, the engineers wrote down the major goals they wanted to accomplish during the day, and at the end of the workday completed another set of questions asking them to reflect on their daily accomplishments, setbacks, habits and ways they could improve their work. After only two weeks of these daily exercises, over 80% of the engineers reported that this short and easy task translated into actionable work strategies and increased productivity. The power of this exercise can be brought to employees on a large scale through technology applications that support well-being in the flow of work. Setting goals for the day or week can help employees focus their energy and prioritize work and well-being tasks that are most personally beneficial. For example, an employee who sets a goal to practice a more positive outlook could get a nudge to take time and practice gratitude during their workday.9

Ultimately, goals will only improve well-being if they are designed with individual needs in mind. Developing a goal-setting framework for well-being requires support from a culture of care (Limeade, 2021). In a framework created by Sirgy (2006), the goals that are the most likely to improve well-being are those that:

- Accommodate employees’ unique needs

- Are meaningful and adaptable

- Address employees’ unmet needs

- Enable employees to grow

- Are selected by employees

- Do not conflict with cultural values, available resources, and other motives or goals

Improve role clarity and remove pain points for employees

When well-being is integrated in the flow of work, employees can have well-being included within their roles. This means that an employee’s schedule, roles and responsibilities are designed with well-being in mind. It also means that well-being should be written in the job description and considered part of the role. HR managers and organizational leaders can conduct job analyses to examine the job tasks and responsibilities and corresponding well-being impacts. For example, job descriptions should be carefully examined to ensure that the workload and tasks are conducive to well-being. For all employees regardless of role, one of the expectations written in the role description should involve supporting the employee’s and team’s well-being. For managers and HR supporting employee well-being in their role will involve ensuring workloads are reasonable, checking in with employees, and allowing flexibility and autonomy whenever possible for employees.

A common roadblock to well-being and productivity is role ambiguity, when employees are uncertain about what is truly expected of them at work. A lack of role clarity can increase employee burnout which is negatively related to employee well-being (Vullinghs et al., 2020). Employees with more ambiguous roles are also at greater risk of quitting (Eys et al., 2005). Role ambiguity can arise from several causes, including the size of a company, frequency of change, micromanagement and vaguely defined tasks (Nyanga et al., 2012). Since some of these factors are partially within managers’ control, it is a good idea to check in with employees periodically to see if they feel confused about their job responsibilities. Where possible, allow employees to “job craft” — the practice by which employees choose what work they do and how they do it. Job crafting enables employees to target ambiguous aspects of their roles directly, which in turn improves well-being and lowers their risk of quitting (Shin et al., 2020).

In addition to improving role clarity, managers and organizations can support well-being by removing pain points for employees. In a typical role, there may be inefficiencies like multiple channels of communication, silos, or “old ways of working” that make the job harder or more frustrating, negatively impacting employee performance and well-being. In addition, employees may be experiencing the effects of larger community and national or global events which serve as stressors. Managers can relieve a variety of pain points by listening to employees and providing flexibility as well as support (Pruitt, n.d.).

Infuse well-being into policies and processes

Incorporating well-being in workplace policies, processes, and company culture has become increasingly important for organizations as the nature of work, the workforce and the workplace continue to change. Shifts, such as the increase of sedentary work, require a greater focus on health-related conditions associated with work and non-work factors rather than those primarily caused by workplace hazards (Schulte et al., 2015). Infusing well-being in organizational policies and processes will have a high return on investment for both organizations and employees (Howard, 2013; Danna & Griffin, 1999). This will also make it more intuitive for organizations to encourage employee well-being in the flow of work.

Employee health and well-being can be affected by many factors; research has found examples such as work stress, degree of job control, conflict between work and life, and lack of organizational support. These and many other factors that affect employee well-being can be managed through policies and processes within organizations. The key areas that can be influenced by healthy workplace initiatives include:

- The psychosocial work environment

- The physical work environment

- Personal health and holistic well-being resources

The psychosocial work environment refers to aspects of organizational culture that impact the mental and physical well-being of employees, including attitudes, values, beliefs and daily practices. Psychological safety is a key element of a psychosocial work environment that supports well-being (Limeade Engage, 2022). Other aspects of a psychosocial work environment include considering well-being when making decisions on scheduling, work arrangements, management practices and communication (WHO, 2010). In a study of shift workers, scheduling practices such as short-notice scheduling, irregular shifts, on-call and cancelled shifts contributed to overall lower well-being in the form of reduced happiness, poorer sleep, and psychological distress (Schneider, & Harknett, 2019). Organizations should determine which policies and practices are most beneficial for employee well-being.

Physical environment refers to the ergonomics, noise, climate, lighting and safety of the workplace (WHO, 2010). Organizations can support employee safety and well-being through policies that address the work environment. For example, policies that ensure a safe working environment, such as ergonomic equipment and freedom to take needed breaks support employee physical well-being and the prevention of accidents. Organizations should also have administrative policies such as mandatory safety training and preventative maintenance as additional policies that support employee well-being (WHO, 2010).

Personal health and holistic well-being resources refer to the health services, information, resources, opportunities, flexibility, and otherwise caring environment provided to workers to support and motivate their efforts to improve or maintain healthy lifestyles. These resources can also be utilized to monitor and support their physical, mental, emotional, financial and work/career health. Examples of organizational personal health resources include employee assistance programs (EAPs), fitness facilities, work breaks for exercise, healthy snack options in the office, and access to confidential medical assessments (WHO, 2010), financial planning and management resources, and resources that improve the overall employee experience (including commitment, engagement and the aforementioned organizational care).

Organizations should incorporate well-being in their work policies and ensure that there is adequate leadership support, resources and communication surrounding well-being implementation (Mellor & Webster, 2013). Once a well-being policy is implemented, organizations must monitor usage to ensure that the culture is supportive and employees are benefiting from these offerings (Zheng et al., 2015).

Support well-being flexibility with tools and resources for self-directed development

Organizations investing in employee well-being need to provide tools and resources so that employees are effectively supported while focusing on their personal well-being needs. Through managers and leadership, organizations should also encourage employees to self-direct their path to well-being. For example, a manager could suggest that their employees reflect on ways that they would like to maintain or improve their well-being. In addition to the space and support for well-being in the flow of work, providing work-life balance, living wages, and opportunities for meaning and shared success are needed for employees to engage in self-directed well-being development (Schulte et al., 2015).

Once employees have selected well-being areas of focus and goals, managers and organizational resources can support employees’ well-being. For example, employees who seek to exercise more would benefit from organizational resources such as tracking their exercise and well-being activities. According to Limeade research, employees who frequently tracked their well-being activities experienced a slight, but statistically significant, increase in exercise frequency when compared across two years. Mental health could be another employee well-being need. For example, an employee who struggles with consistent symptoms of anxiety could utilize workday schedule flexibility, EAPs and/or meditation activities. With the information provided by their manager, this employee can identify and pursue resources such as a flexible work schedule, bio tracking tools (e.g., watch), group fitness challenges, and Employee Resource Groups (ERG) that support balancing work, while increasing exercise and social connection, all of which are known to help with anxiety. These tools and resources can support employees during their well-being journey. It is important to offer resources that support well-being in a variety of domains to support widely diverse employee needs.

Ground-breaking research has begun to incorporate biometrics that predict whether an employee is focused and in the flow at work with up to 70% accuracy (Rissler et al., 2020). Such technology could potentially learn the correct time to nudge an employee to take a well-being break. Microsoft recently conducted a study that found 77% accuracy for recommended break nudges during work activities (Kaur, 2020). However, technology has the potential to be more disruptive than helpful if it is not set up thoughtfully and intentionally. Companies should be wary of technologies that use a consumer-focused approach, which use overwhelming and engrossing strategies to keep the individual engaged with the platform as much as possible. In practice this may look like immediate notifications following a ‘like’ on social media to pull your attention to the platform or continuous streaming content such as new a tv series or music queued up after finishing the album or series. Often these approaches use frequent nudges that can lead to increased task switching and decreased employee productivity. There are a couple of important considerations when incorporating technology to nudge and support well-being habits. The first consideration is privacy concerns for employees. Organizations should only collect data necessary for supporting employees’ well-being. In addition, data should be de-identified and never connected with performance evaluations (Brassart, 2020). Another consideration is the possibility of causing disruptions through the use of notifications and nudges. One study captured this potential disruption by having employees work with a cell phone present: simply having a cell phone present decreased productivity by up to 40% (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2012). While the purchasing of smart phones has more than doubled since that study, we can appreciate the influence of frequent distractions, in the form of nudges or notifications, and subsequent need for a more holistic approach (Patterer et al., 2021). However, as mentioned in the Microsoft study, nudge timing can reach high levels of accuracy (Kaur, 2020).

Research by Nielsen et al. (2017) found that all well-being resources tested were equally effective for boosting employee well-being and performance. The research showed that any type of well-being resource was helpful for countering job demands. To determine which specific well-being resources to invest in, organizations should survey employees. According to employees surveyed by TINYpulse by Limeade, the top four resources helpful for supporting employee well-being include: 1) time off for exercise; 2) ergonomic office equipment; 3) EAPs; 4) healthy food offerings in the office (TINYpulse, SOEE Q1, 2022). When selecting well-being resources, HR leaders should select technology that is capable of nudging and tracking progress while employees are building healthy habits. To ensure high levels of usage, the technology should be easily integrated into employee workflow so that they can access well-being in the flow of work.

Create a culture of well-being with leadership support and employee listening

Infusing well-being in the flow of work is a key factor for supporting a company culture of well-being. When the culture, environment, technology, resources, policies, and cues all support well-being, employees can make healthy choices more frequently and with less effort (Gunther et al., 2019). Although culture change is a challenging endeavor, the desire for well-being at work has increased among employees. On top of increased demand for well-being support, the disruption to work from the COVID-19 pandemic and the ‘great resignation’ has created an atmosphere ripe for culture change in organizations (Nayal et al., 2021). Now is the ideal time to evolve company culture to better support employee well-being, and organizations can begin with steps that would support and enhance a desired culture change. A well-being focused culture will make it easier for employees to discover, access and use well-being resources.

The first step to creating a well-being culture is garnering leadership and managerial support. According to researchers, leadership support strengthens the relationship between human resource (people-centric) practices and employee well-being (Zhang et al. 2020). Next, design and implement an employee listening strategy comprised of surveys, stay interviews, and 1-on-1 check ins with managers. Share back the listening results along with the strategy for improving employee well-being. It is important for the strategy to be heavily informed by the employee feedback gathered in the previous step. Enlist leaders and managers for communicating and building support for well-being initiatives and culture. According to Kreiner (2006), managers’ behaviors and the workplace culture play a key role in encouraging employees to keep boundaries at work to support their holistic well-being. Ensure the provision of tools, 13

technology, processes and systems to enable flexible and productive collaboration, work schedules, and communications to help leaders, managers, and employees align and do their best work. Throughout the process of implementing well-being initiatives, organizations, leaders, and managers should continue to monitor reactions and outcomes through employee listening strategies.

Infusing well-being in the flow of work will remove barriers and increase employee well-being and productivity. Support for employee well-being typically includes resources, technology to track and provide well-being reminders, and a strong culture that promotes care and well-being. Well-being practices will vary between organizations, but the desired goal, for all employees to feel good and to live with purpose, remains the same. Organizations seeking to support employee pain points, infusing well-being into policies and practices, supporting flexibility and self-directed well-being through resources, and creating a culture of care and employee listening.

Basadur, M., Basadur, T., & Licina, G. (2012). Chapter 26—Organizational Development. In M. D. Mumford (Ed.), Handbook of Organizational Creativity (pp. 667–703). Academic Press. https://doi. org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374714-3.00026-4

Berry, L. L., Mirabito, A. M., & Baun, W. B. (2010). What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs. Harvard business review, 88(12), 104-112.

Brassart Olsen, C. (2020). To track or not to track? Employees’ data privacy in the age of corporate wellness, mobile health, and GDPR. International Data Privacy Law.

Chari, R., Chang, C. C., Sauter, S. L., Sayers, E. L. P., Cerully, J. L., Schulte, P., … & Uscher-Pines, L. (2018). Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health a new framework for worker well-being. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 60(7), 589.

Conti, M. E., Arcuri, M., & Simone, C. (2018). Wellbeing, conflict and teamworking: the social role of the team leader-an overview. International Journal of Environment and Health, 9(2), 151-168.

Eys, M. A., Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R., & Beauchamp, M. R. (2005). The Relationship Between Role Ambiguity and Intention to Return the Following Season. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(3), 255– 261. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200591010148

Fletcher, T. (2020). The Role of Wellbeing & Resilience in Diversity. Diverse Educators.

Gunther, C. E., Peddicord, V., Kozlowski, J., Li, Y., Menture, D., Fabius, R., … & Nigro, P. J. (2019). Building a culture of health and well-being at Merck. Population Health Management, 22(5), 449- 456.

Harter, J. (2022). Percent Who Feel Employer Cares About Their Wellbeing Plummets.

Inceoglu, I., Thomas, G., Chu, C., Plans, D., & Gerbasi, A. (2018). Leadership behavior and employee well-being: An integrated review and a future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 179-202.

Huang, Q., Xing, Y., & Gamble, J. (2019). Job demands–resources: A gender perspective on employee well-being and resilience in retail stores in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(8), 1323- 1341.

Kanfer, R., Frese, M., & Johnson, R. E. (2017). Motivation related to work: A century of progress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 338-355

Kaur, H., Williams, A. C., McDuff, D., Czerwinski, M., Teevan, J., & Iqbal, S. T. (2020, April). Optimizing for happiness and productivity: Modeling opportune moments for transitions and breaks at work. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15).

Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 27(4), 485–507. Error! Hyperlink reference not valid. doi.org/10.1002/job.386 Limeade Institute: The Science of Care; September 2019. Limeade Institute: Employee Care Report; April 2021 Limeade Institute: Psychological Safety for Today’s Workforce – Limeade; February 2022.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Nayal, P., Pandey, N., & Paul, J. (2021). COVID‐19 pandemic and consumer‐employee‐organization wellbeing: A dynamic capability theory approach. Journal of Consumer Affairs.

Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101-120.

Nieuwenhuis, R., & Yerkes, M. A. (2021). Workers’ well-being in the context of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Community, Work & Family, 24(2), 226-235.

Nyanga, T., Mudhovozi, P., & Chireshe, R. (2012). Causes and Effects of Role Ambiguity as Perceived by Human Resource Management Professionals in Zimbabwe. Journal of Social Sciences, 30(3), 293– 303. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2012.1189 3006

Maggiori, C., Johnston, C. S., Krings, F., Massoudi, K., & Rossier, J. (2013). The role of career adaptability and work conditions on general and professional well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 437-449.

Meyer, J. P., & Maltin, E. R. (2010). Employee commitment and well-being: A critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. Journal of vocational behavior, 77(2), 323-337.

Meyer, A. N., Murphy, G. C., Zimmermann, T., & Fritz, T. (2019). Enabling good work habits in software developers through reflective goal-setting. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 47(9), 1872-1885.

McHugh, M., Farley, D., & Rivera, A. S. (2020). A qualitative exploration of shift work and employee well-being in the US manufacturing environment. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 62(4), 303-306.

Pruitt, J. (n.d) How solving employee pain points boosts culture and moral. Inc.com

Patterer, A. S., Yanagida, T., Kühnel, J., & Korunka, C. (2021). Staying in touch, yet expected to be? A diary study on the relationship between personal smartphone use at work and work–nonwork interaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology.

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2012). Can you connect with me now? how the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 237–246. https://doi. org/10.1177/0265407512453827

Putnam, L. (2015). Workplace wellness that works: 10 steps to infuse well-being and vitality into any organization. John Wiley & Sons.

Rollins, A. L., Eliacin, J., Russ-Jara, A. L., Monroe-Devita, M., Wasmuth, S., Flanagan, M. E., Morse, G. A., Leiter, M., & Salyers, M. P. (2021). Organizational conditions that influence work engagement and burnout: A qualitative study of mental health workers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 44(3), 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000472

Rissler, R., Nadj, M., Li, M., Loewe, N., Knierim, M. and Maedche, A., 2020. To Be or Not to Be in Flow at Work: Physiological Classification of Flow using Machine Learning. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, pp.1-1.

Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2019). Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 82-114.

Schulte, P. A., Guerin, R. J., Schill, A. L., Bhattacharya, A., Cunningham, T. R., Pandalai, S. P., … & Stephenson, C. M. (2015). Considerations for incorporating “well-being” in public policy for workers and workplaces. American journal of public health, 105(8), e31-e44.

Shin, Y., Hur, W.-M., Park, K., & Hwang, H. (2020). How Managers’ Job Crafting Reduces Turnover Intention: The Mediating Roles of Role Ambiguity and Emotional Exhaustion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113972

Sirgy, M. J. (2006). Developing a Conceptual Framework of Employee Well-Being (EWB) by Applying Goal Concepts and Findings from Personality-Social Psychology. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1(1), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11482-006-9000-4

Sirgy, M. J., Lee, D. J., Park, S., Joshanloo, M., & Kim, M. (2020). Work–family spillover and subjective well-being: the moderating role of coping strategies. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(8), 2909-2929.

Smith, Ryan. 2020. How CEOs Can Support Employee Mental Health in a Crisis. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/05/ how-ceos-can-support-employee-mental-health-in-a-crisis

Stansfield, T. C., & Longenecker, C. O. (2006). The effects of goal setting and feedback on manufacturing productivity: A field experiment. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 55(3–4), 346–358. https://doi. org/10.1108/17410400610653273 TINYpulse. SOEE Q1 2022. https://www.tinypulse.com/hubfs/ SOEE%20Q1%202022.pdf

Umstot, D.D., Bell, C.H., & Mitchell, T.R. (1972). Effects of job enrichment and task goals on satisfaction and productivity: Implications for job design. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(4), 379-394.

Vullinghs, J. T., De Hoogh, A. H., Den Hartog, D. N., & Boon, C. (2020). Ethical and passive leadership and their joint relationships with burnout via role clarity and role overload. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(4), 719-733.

World Health Organization. (2010). Healthy workplaces: A model for action: for employers, workers, policy-makers and practitioners. World Health Organization.

Zhang, X., Lin, Z., Liu, Y., Chen, X., & Liu, D. M. (2020). How do human resource management practices affect employee well-being? A mediated moderation model. Employee Relations: The International Journal.

Zheng, C., Molineux, J., Mirshekary, S., & Scarparo, S. (2015). Developing individual and organisational work-life balance strategies to improve employee health and wellbeing. Employee Relations. 37(3), 354-379.

Zwetsloot, G., Leka, S., & Kines, P. (2017). Vision zero: from accident prevention to the promotion of health, safety and well-being at work. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 15(2), 88-100.

Explore more insights from Limeade

Reading List

17 books to cultivate professional and personal self-care from the inside out

There's no better time than now to focus on what matters most — you. These must-reads will arm you on the road to self-care — both at home and at work.

Guide

5 ways to create a personalized employee experience

Enter the new era of personalized well-being — a seamless employee experience that reflects who each employee is and how they work.

Guide

Employee engagement software: Your ultimate guide

Improving employee engagement has been shown to increase profitability, improve retention, and attract higher-quality employees – making employee engagement software a pivotal part of office life and culture. But getting started and finding all the right information on which software to choose can seem like a daunting task.

Guide

How to build a business case for employee wellness programs

This guide walks through the importance of a wellness program, the information you need to build a business case for an employee wellness program, and the cost savings and business benefits enabled by a holistic approach to well-being with Limeade.